What does 'urban' mean?

And is the alternative to it 'suburban' or 'rural'?

Discussions about urban geography and planning often include the term urban. But what do we mean when we say “urban,” and what is the alternative or opposite? And how can you examine a place and determine whether or not it’s urban?

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this and have decided that it really involves a mix of four distinct factors:

- Density

- Regional population

- “Soft factors”: architecture, urban design, social issues

- Transportation

To improve our discussion of these issues, it’s best to use as specific language as possible.

Density

Perhaps the easiest way to quantitatively classify an area as urban or not is based on population density (or household density). This is a spectrum from high-density to low-density, where we usually think of high-density as urban, low-density as rural, and the middle of the spectrum as suburban.

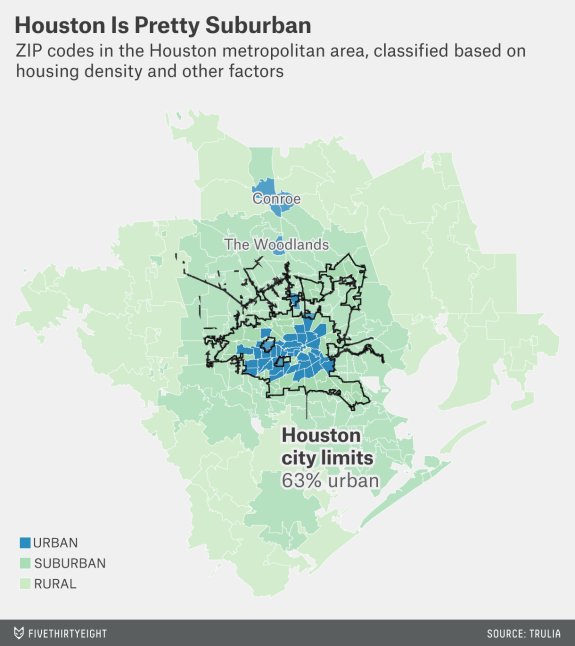

Where do you draw the lines between urban, suburban, and rural? FiveThirtyEight/Trulia addressed this issue in a fascinating study of how people describe where they live. Their findings:

Our analysis showed that the single best predictor of whether someone said his or her area was urban, suburban or rural was ZIP code density. Residents of ZIP codes with more than 2,213 households per square mile typically described their area as urban. Residents of neighborhoods with 102 to 2,213 households per square mile typically called their area suburban. In ZIP codes with fewer than 102 households per square mile, residents typically said they lived in a rural area.

See their analysis of Houston:

Their findings seem to make intuitive sense, matching the popular perception of older northern cities as more urban and newer Sunbelt cities as suburban:

By this measure, many large cities are overwhelmingly urban. Among the 10 largest cities, New York, Chicago and Philadelphia are at least 95 percent urban. Outside the largest 10, San Francisco, Detroit, Seattle, D.C., Baltimore and Boston are also entirely urban or nearly so. Los Angeles — despite its reputation for sprawl — is 87 percent urban. But three of the 10 largest cities are mostly suburban, including San Diego (49 percent urban), San Antonio (35 percent urban) and Phoenix (30 percent urban).

I’ll return to the subject of Los Angeles later.

While pretty good, the density method isn’t perfect. Low-density areas within dense, large cities might be counted as rural. Meanwhile, dense areas of tiny towns might qualify as urban; the study noted that “Residents of very small cities and towns rarely said they lived in an urban area, even if their neighborhood was quite dense.”

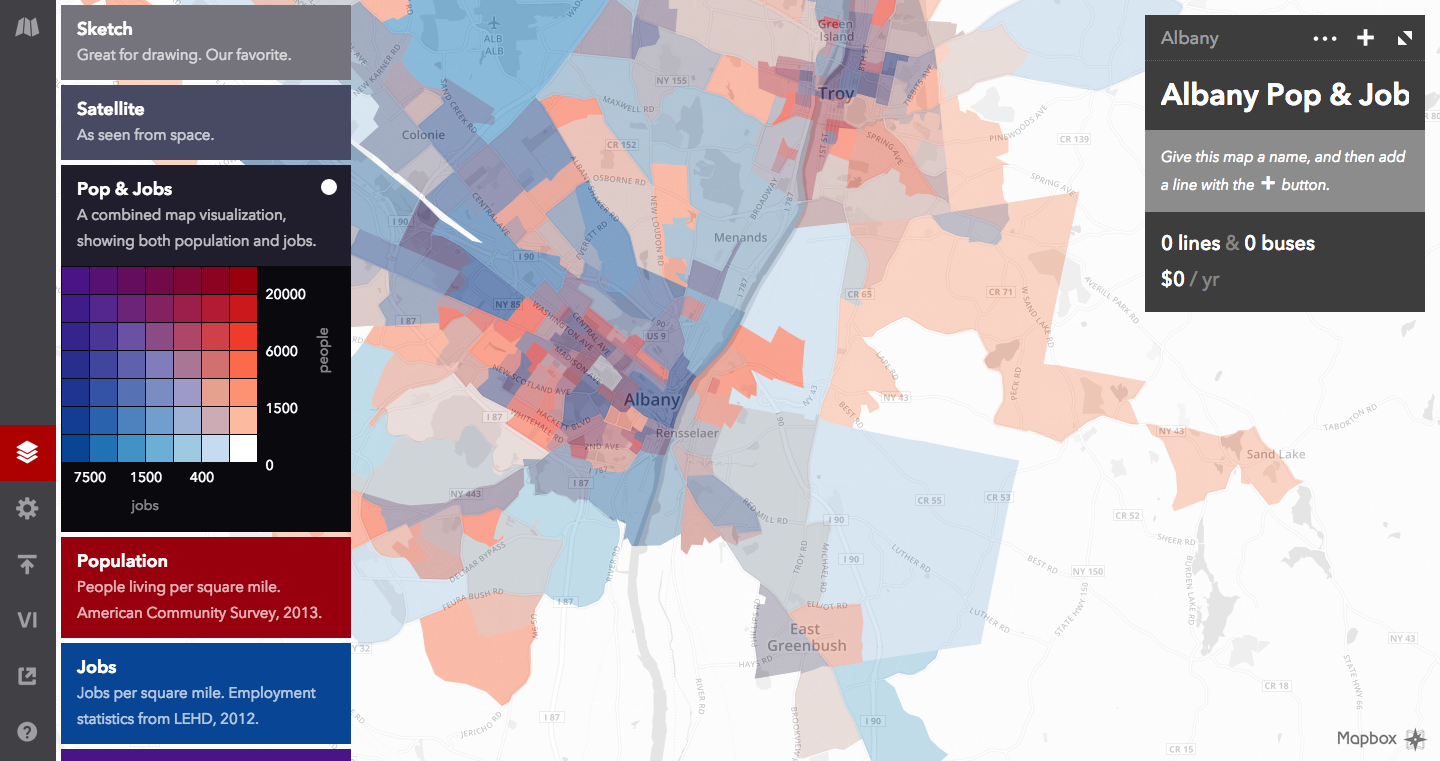

Note that there’s a second sort of density we can talk about: jobs. It’s fairly common for downtowns to have a lower population density than some inner residential neighborhoods due to an overwhelming number of office buildings downtown. And in a more general sense, areas with a lot of commercial activity might have more “stuff” than you would figure just by looking at population density. The FiveThirtyEight/Trulia study noted that “Residents of lower-density ZIP codes with lots of businesses sometimes called their neighborhoods urban.”

Remix, an amazing transit planning tool, handles this population vs. jobs density issue by displaying both in a single layer:

Job density is also a great figure because it is a proxy for several other things. Since many jobs are public-facing, areas with high job density are also likely to have a high density of stores, institutions, and other destinations that attract people besides their own employees, making them activity centers.

Regional population

An alternative way of approaching this issue is from a broader perspective: classifying entire regions as urban. The Census Bureau does this.

- They define an urbanized area as “densely developed territory that contains 50,000 or more people.” The density isn’t really that important as long as the area is continuously built-up, and thus this includes many areas that would be considered suburban by the population density standard.

- The Census Bureau also has a concept called urban clusters: “densely developed territory that has at least 2,500 people but fewer than 50,000 people.” This is mainly to capture towns that lie outside of urbanized areas but are still of a non-trivial size.

- Any place that is not part of an urbanized area or urban cluster is considered rural.

This classification approach misses most details about whether or not you’d call an individual neighborhood urban (beyond whether or not it’s part of an urban area). Still, it’s useful for looking at national statistics, as you can examine data on people who live in urban areas versus rural areas.

“Soft factors”: architecture, urban design, social issues

Beyond the quantitative factors listed above, there are many subjective issues — particularly regarding appearance — that affect how urban a place feels. (For now, I’ll exclude most attributes associated with transportation, as that gets a whole section.)

Things that make a place feel “urban,” depending on who you talk to, include:

- Skyscrapers

- Public housing, especially if it’s in a group of large buildings (sometimes nicknamed “the projects”)

- Large train stations and bus terminals

- Blighted buildings and abandoned property

- Street crime and gangs

- Concentrated poverty

As noted in the FiveThirtyEight/Trulia study, “Residents of lower-income neighborhoods with older housing stock often said they lived in an urban area, even if it was lower-density.”

The list of attributes that make a place seem “suburban” isn’t as long or salient as the urban list, but a prominent example might be vinyl siding — and more generally, cheap building materials. Of course, this can also be found in plenty of big cities. For example, the Philadelphia Housing Authority has created a number of developments that include cookie-cutter suburban-style houses:

I’ve never been a fan.

Let’s have a look at Las Vegas Strip (image source):

There’s a high density (at least of jobs and visitors), it’s part of a large urbanized area, and we see plenty of large buildings that might be considered small skyscrapers. Yet some urbanists might still feel there’s an “anti-urban” element. Meanwhile, recall that Los Angeles has a fairly high density — not to mention being a major urbanized area and having most of the “urban” soft factors listed above — yet many people perceive it to be suburban. Why?

Cars. Los Angeles and Los Vegas are both very car-dominated places, bringing us to our last issue: transportation.

Transportation

I’ve noticed a lot of urbanists have this idea that “urban” places are pedestrian-, bike-, and transit-friendly, while “suburban” places are car-oriented. This sort of makes sense, but there are several problems.

- If being car-oriented is suburban, then what about rural areas? Are they not car-oriented? (It’s true that rural areas tend to do without some classic suburban features like shopping malls and stroads. But still.)

- This notion assumes there’s a correlation between being pedestrian-, bike-, and transit-friendly. While this is partially true, it partially isn’t.

- This presents a false dichotomy. Being pedestrian-, bike-, and transit-friendly are not necessarily all opposed to being car-friendly.

I think a better way to think of transportation is that a place can be friendly toward some combination of pedestrians, bikes, transit, and cars, and while it’s generally hard to pull off all four, they can come in a variety of combinations. Let’s see a few that defy the stereotypical urban/suburban transportation ideals:

Transit- and car-friendly areas

Silver Spring, MD (which borders DC) is one of the best examples. It’s a very dense area centered on a Metro station with very frequent service — usually about every 6 minutes — and a transit center serving many local bus lines.

It’s not so great for pedestrians and bicyclists. Turn around from the Metro station and you’re greeted with wide suburban arterials roads that are quite a challenge to cross and don’t do much to slow car speeds.

This pattern can be found throughout the DC suburbs. Over in Arlington, Crystal City consists of many large buildings in close proximity to a Metro station (again, with frequent service). Yet it centers on an enormous highway.

It’s a total abomination for pedestrians and bicyclists. And the highway is named after Confederate president Jefferson Davis!

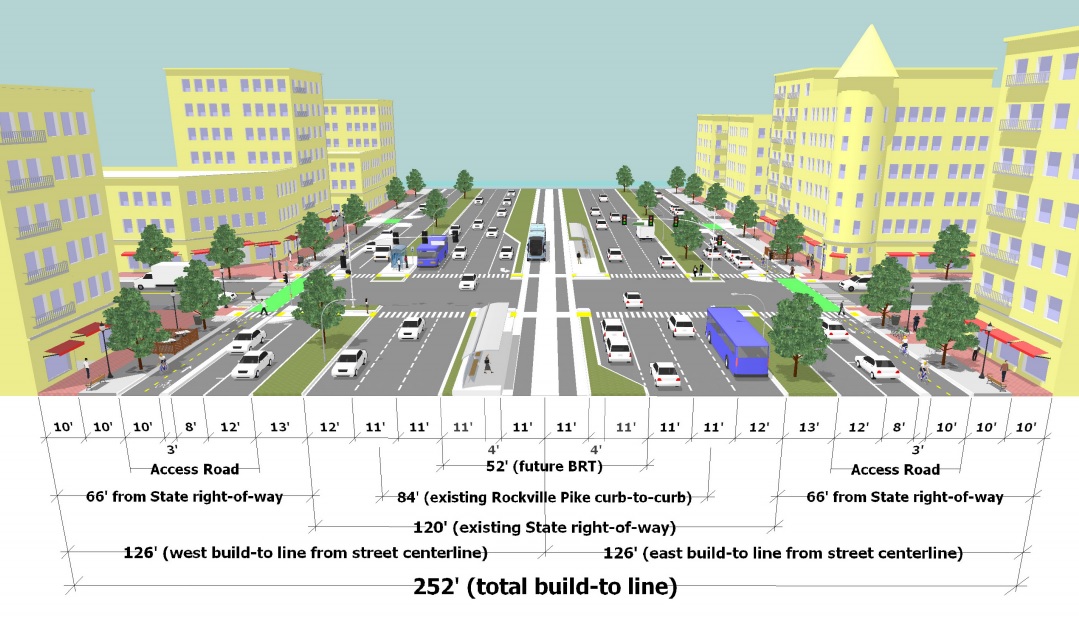

Rockville, MD, is trying to do better, yet their proposal for making Rockville Pike more multi-modal seems to offer little progress from the status quo:

More generally, many features that make places car-friendly also make them bus-friendly… though they might not be as friendly to the pedestrians trying to access those buses.

Bike- and car-friendly areas

The Netherlands and Denmark are famous for being some of the most bike-friendly countries in the world, and for good reason. And while they are often thought of for their urbanism, they still managed to build plenty of car-friendly suburbs. These suburbs often look a lot like American suburbs, yet they still have plenty of bike infrastructure.

Conflict between bike- and transit-friendliness

Speaking of Denmark and the Netherlands, numerous observers have pointed out that policies intended to promote bike usage may have the effect of reducing transit usage. Modal split data from European cities shows that those with a notably high bike mode share often have a lower transit mode share than comparable cities — though it’s admittedly hard to know if bicycling is actually drawing from transit or walking or driving. Copenhagen and Vienna have similar percentages of people commuting by car, but Vienna has a higher mode share for transit and walking, while Copenhagen has a higher mode share for bicycling.

In terms of street geometry, bikes and transit can sometimes run into problems, particularly when bikes and buses/streetcars have to share a lane and when streetcar stops interrupt bike lanes. Streetcar tracks can also pose a hazard for bike wheels, which can get caught in them, sometimes leading to cyclist injury.

Conflict between pedestrians and bicyclists

Walking and biking are often thought of together, but unfortunately they do come into conflict. There are a number of places where this is true, among them:

- multi-use trails

- pedestrians plazas

- sidewalks (specifically, people biking on them)

- bike lanes vs. jaywalkers

You can read an endless list of articles on this topic.

The upshot

Defining “urban” and “urbanism” is complicated.

From a statistical perspective, the first two factors (density and regional population) make the most sense, and are useful for discussing aggregate statistics. From a “feelings” perspective, particularly regarding specific locales, all four factors apply.

How will this affect the language I use?

- I will try not to say that places “seem urban.”

- I will try to use as specific language as possible.

- I will use “promoting urbanism” to mean something like “making a place more pedestrian-, bike-, and transit-friendly and increasing density” — or as Andrew Price put it, increasing the ratio of places to non-places. As much as I like using specific language, it’s also nice to not have to repeat a verbose description over and over, so I’m pretty fine with saying “urbanism” with this specific meaning in mind. (See Jarrett Walker’s post on this issue.)

What do you think?